SPECIAL REPORT | In 2015, the fate of seven Orang Asli children lost in the jungle of Kelantan brought the issue of Orang Asli education into mainstream attention for the first time.

Five of the children died, but two survived after a 47-day ordeal in the wild. They said they ran into the jungle as they feared punishment from a teacher who caught them swimming in the river.

The case elicited promises of improvement in the quality of care for Orang Asli children, some leaving home as young as seven to attend residential schools far away.

However, dropout rates among the Orang Asli children indicate there is not much improvement.

Last year, 26,571 Orang Asli pupils enrolled in primary schools, but only 13,155 registered for secondary schools.

This year, the number of Orang Asli pupils in primary school is comparable at 26,126 pupils but secondary school enrolment went down to 11,729 students.

Things get worse at the secondary school stage. Of the 100 secondary school Orang Asli students tracked in a Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) study in 2013, only six of them reached Form Five.

Shaq Koyok, a young Orang Asli artist who won the Merdeka Award in 2017 for his impactful work, said the high dropout rate means very few Orang Asli children make it to tertiary education.

“When I was in university, there was only one other Orang Asli student in the whole undergraduate programme. Just imagine the same situation for the Malay, Chinese and Indian communities.

“There would, quite rightly, be outrage. Yet this is the situation for the indigenous people of this country,” Shaq said.

‘Colonised and ignored’

Long travel distances from home to school have previously been cited by government officials as a reason for the high dropout rate, but Shaq believes the issue is beyond logistics.

He said for many Orang Asli children, what is taught in school is alien and unrelated to their way of life.

“Sometimes it feels like we are being colonised and ignored,” he said.

The lack of recognition for Orang Asli heritage, culture and way of life in the curriculum is a double-edged sword.

Colin Nicholas, a forefront researcher and activist for Orang Asli rights, says that when children are plucked out of their communities and placed in residential schools, it is a sort of forced assimilation.

“Particularly with the hostel system where Orang Asli children from seven years old are kept away from their families and their culture for much of the school year and taught a new language, a new culture and often, introduced to a new religion.”

Although officials stress any religious conversion by minors must be done with parental consent, the pupils receive exposure to other religions, such as Islam, in school and lose connection with their traditional beliefs.

“You would expect in one generation to see many Orang Asli students who are no longer rooted in their language, culture and traditions,” Nicholas said.

Bullied and taunted

At the same time, the failure of the curriculum to recognise Orang Asli culture means their classmates have no understanding of who they are and taunt them for being different.

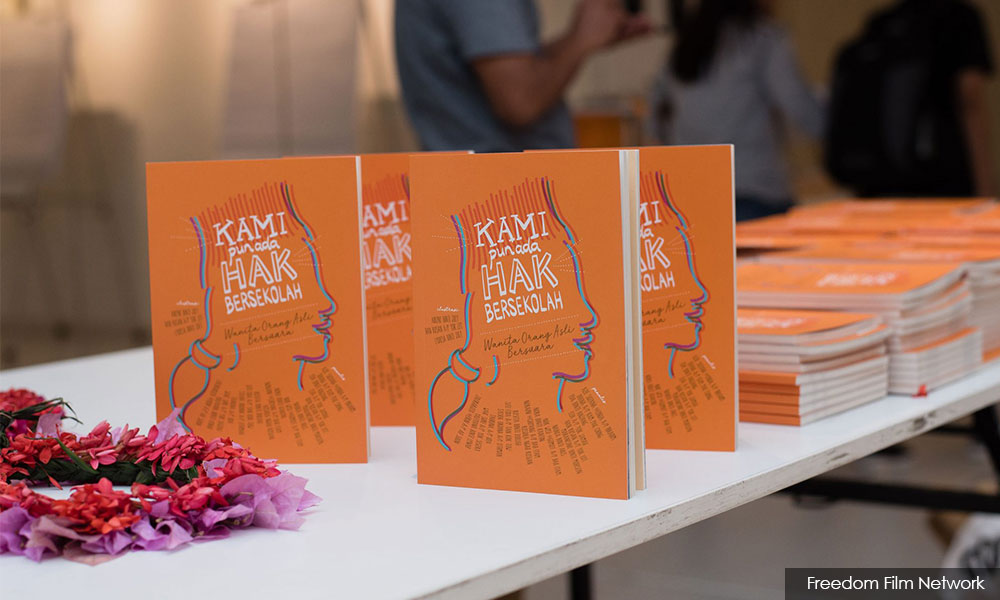

In a recently-launched book compiling the experiences of Orang Asli girls in education, many contributors recall being called names and bullied for being Orang Asli.

The girls - some of them now women - recall how they were taunted by schoolmates who deemed Orang Asli people as “stinky” or “stupid” and mocked them for “eating frogs”.

The students seemed to have picked it up from the teachers - one Orang Asli woman recalled how a teacher called her "orangutan" while another said she was told by a teacher it was easier to teach a monkey than an Orang Asli child.

Some of these students, like Eda Anjang, were taunted so badly they dropped out of school.

Soon after starting Form 3 in a new school, Eda’s classmates bullied her and forced her to do their homework. When she refused, they soiled or threw away her school uniform.

“I was angry with their behaviour towards me,” she wrote. “But I could only be silent as I was a new student. I decided to quit school because I could not stand the bullying,” she wrote in the book Kami Pun Ada Hak Bersekolah: Wanita Orang Asli Bersuara.

Brenda Danker, part of the team who compiled the book, said it is tough for Orang Asli girls.

“Orang Asli girls have it even more difficult because when they drop out of schools, they tend to be less mobile and are at risk of an early marriage.”

'Stop trying to change us'

Jenita Engi, a Temuan activist, said underlying the torment is a belief that the Orang Asli must abandon their ways and modernise.

“Malaysia needs to get rid of this mentality that the indigenous people need to change their way of life if they want development.

“This must be changed because what Malaysia needs to do is to protect and preserve the Orang Asli identity using their language and the environment they live in,” Jenita said.

She said this was especially important for those who lived in the interior and who should not be forced out of their way of life.

“Assist them (to preserve their culture). Don’t pressure them to assimilate and become another race,” Jenita added.

Part 1: Orang Asli voices may go silent as languages face extinction

Part 2: Once deemed 'wildlife', Orang Asli still face condescension